Blog

Carbon Farming in France and in the United States: Between Hopes and Realities

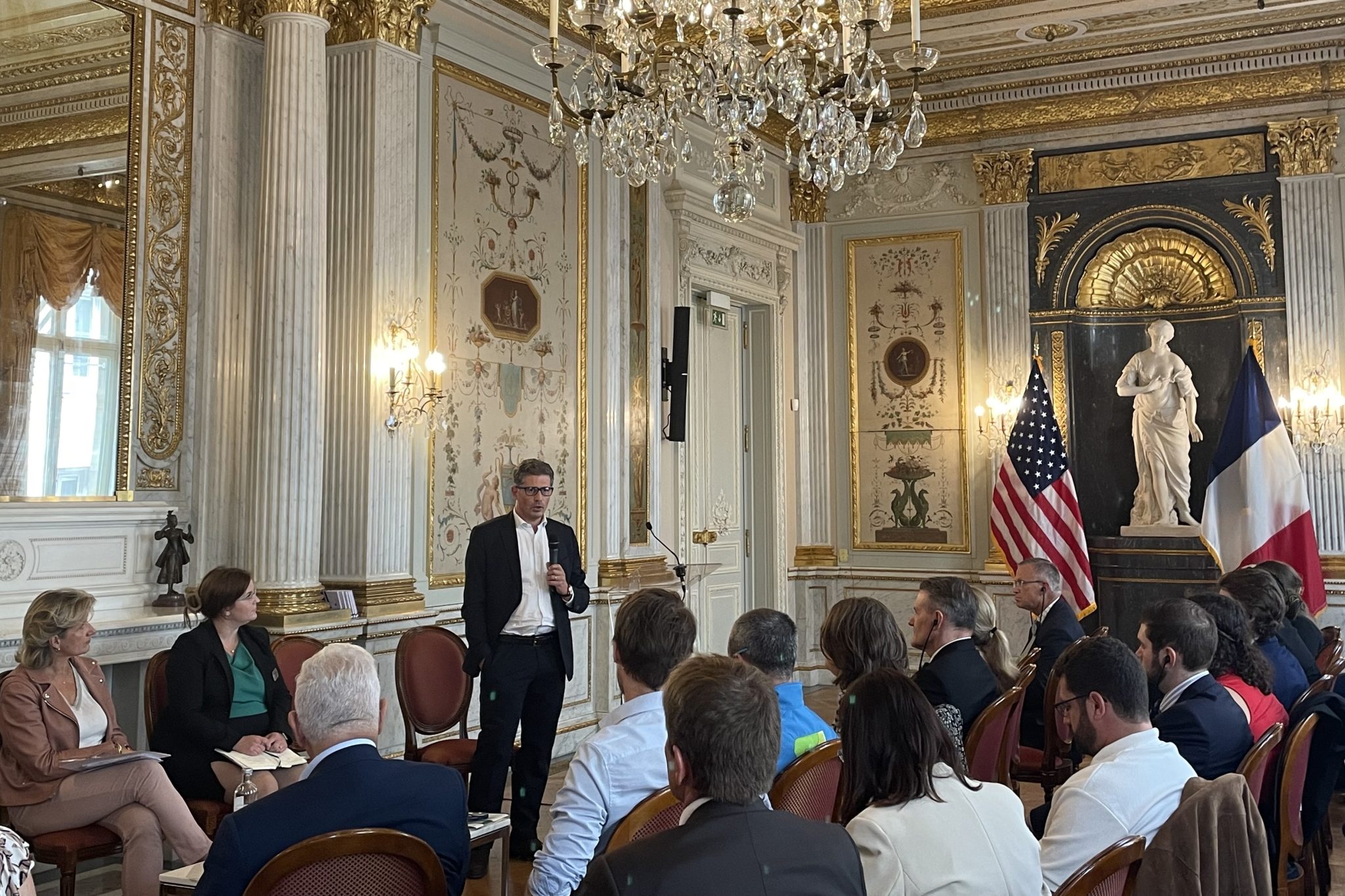

On September 1st, 2023, Farm Foundation and the French think tank Agridées gathered their networks at the invitation of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) office of the U.S. Embassy in Paris to take stock of the hopes and realities surrounding low-carbon agriculture. The event brought together a variety of players who are helping farmers make the transition to low-carbon farming, and who shared their experiences. Below are the key points from the conversation.

- Strong public incentives for the transition to low-carbon agriculture

As signatories to the Paris Climate Agreement, our two countries are aiming for climate neutrality by 2050. Various policy levers are therefore being put in place to encourage the decarbonization of the economy, with a specific focus on agriculture. In France, the national Low carbon strategy (Stratégie Nationale Bas Carbone) imposes guidelines and paths for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050, and the Ministry of Ecological Transition has set up a carbon certification framework (the Label Bas Carbone) to reward the efforts of economic players to reduce their emissions and store carbon. In the United States, there is a long-term strategy including pathways to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050[1]. The government is encouraging nature-based solutions[2], and in particular climate-smart agriculture and forestry[3], with its conservation agriculture practices to increase soil carbon storage, says Garth Boyd, a partner in the consulting firm The Context Network and Farm Foundation Round Table Fellow.

- Numerous private players are supporting farmers in their low-carbon transition

Changing practices to reduce GHG emissions and store more carbon is a complex, technical, and costly operation for farmers. That is why a number of private players are helping them to make the transition.

In France, this is the case at Terrasolis, an innovation hub or low-carbon agriculture, which piloted the CarbonThink project, pointed out Carole Leverrier, director of Terrasolis. For his part, Edouard Lanckriet, development director at Agrosolutions, part of the InVivo Group, presented the consulting firm’s role in the drafting of the Label Bas Carbone methodology for field crops, and has developed Carbon Extract, a support tool for cooperative technicians and farmers. Similarly, Anaël Bibard, president of FarmLeap (a platform that uses farmers’ data to improve their performance), and also president of the Climate Agriculture Alliance (which brings together a number of European companies specializing in low-carbon agriculture), stressed the need for these players to work together to ensure that their actions are both coherent and impactful.

On the U.S. side, François Guérin, director of government affairs for Europe, Middle East and Africa at ADM International, broadened the subject of low-carbon agriculture to include regenerative agriculture. He presented his company’s commitment to this type of agriculture in order to reduce GHG emissions, improve soil health, protect water quality and biodiversity, sequester carbon and improve farm resilience[4] . ADM is working to develop sustainability indices by working with companies such as Farmers Business Network, a specialist in agricultural data[5].

- Manufacturers are turning away from the carbon finance market (offsetting), preferring to decarbonize their own value chains (insetting).

For Edouard Lanckriet, voluntary carbon finance is not adapted to agriculture. It was created for other sectors where the permanence of carbon storage is not an issue. This is not the case for agricultural carbon storage. Specific rules must therefore be devised for voluntary agricultural carbon finance.

The problem of farmers double-counting their decarbonization efforts was highlighted by Anaël Bibard, who insisted on the need for collaboration between stakeholders o avoid this problem: efforts made by the same farmers but in different programs may in fact be counted several times (for example, one relating to a sector and the other to the entire farm), due to a lack of consistency between accounting systems.

The transparency of measurement, reporting and verification (MRV) methods based on the data collected is one of the keys to robustness, and therefore to confidence in the carbon credits generated. Each method makes different choices between modeling (based on drone or satellite imagery) and soil analysis, and must strike a balance between competitive pricing (which restricts the number of soil analyses), time spent collecting agricultural data compatible with the schedules of the farmer and his advisor, the quantity and quality of the raw data needed to feed the mathematical models, and finally the reliability of the latter. Anaël Bibard and Edouard Lanckriet agreed on this point, stressing the role of digital farm management systems to collect, store and manage several hundred to several thousand data points for each farm. The key is to build credible programs, summarized Garth Boyd.

The latter highlighted a number of past failures that have undermined the confidence of producers and buyers of agricultural carbon credits. While certain carbon offset certification frameworks such as VCS or Gold Standard are internationally recognized, some programs using them have revealed flaws in the implementation of practices. Similarly, a carbon exchange opened in Chicago (the Chicago Climate Exchange), but failed in 2010 after a ten-year effort. Carbon prices collapsed due to a lack of verification and robustness in the quality of carbon credits. There’s plenty to give pause to farmers and buyers who wanted to get started.

In the end, the reason why voluntary agricultural carbon finance is not developing more in the form of offsetting schemes is due to a lack of confidence in the quality of the carbon credits generated by farmers: are they permanent? are they calculated correctly? The transition to low-carbon agriculture, and more broadly, regenerative agriculture, is today better financed by insetting premiums corresponding to Scope 3 emissions, which are simpler to set up and meet the specifications set by the food industry itself, without going through carbon finance, notes Garth Boyd.

He pointed out that various companies use the Greenhouse Gas Protocol to measure, account for and manage their emissions. Examples include McDonald’s, Corteva, BASF and Unilever. The Protocol distinguishes three different emission scopes: direct emissions in Scope 1, indirect emissions linked to energy consumption in Scope 2, and other indirect emissions (upstream and downstream) in Scope 3.

For his part, Edouard Lanckriet pointed out that the international Science-Based Targets (SBTi) methodological framework has been chosen by many companies to decarbonize their Scope 3. How can we link decarbonization frameworks for agricultural production, such as the French Label Bas Carbone, and those for industrial transformation, such as SBTi? Unfortunately, this issue has not yet been resolved[6] .

- Farmers looking for value: “Show me the money“

“Show me the money”: that’s how Garth Boyd sums up the attitude of farmers, who only take the risk of committing to these transitions if there’s a return on investment (new farm equipment, new seeds, and plant cover in particular). They are looking for a return on their investment after having shared their technical and economic data with MRV tool suppliers, which of course requires data privacy guarantees.

According to Anaël Bibard, only 3% of farmers are engaged in these transitions with precision agriculture. To increase adopting significantly, data management is not the only issue. It is necessary to support the use of data, it is also necessary to acculturate farmers to these practices and maximize their efficiency.

The results of the CarbonThink project supported by Terrasolis showed that the carbon footprint reduction potential for field crops was only 20% using the Label Bas Carbone’s field crops methodology, which is not very much, but is already a good lever for getting the process underway. For Carole Leverrier, the low-carbon approach needs to be complemented by co-benefits to attract more farmers to this transition, thus moving closer to the regenerative agriculture approach.

Conclusion

For the time being, isn’t the value concentrated on the one hand with consultancies and companies providing costly MRV tools, and on the other with agri-food manufacturers who promote low-carbon or regenerative agriculture as a marketing tool? This raises two questions. Which link(s) in the value chain is (are) legitimate to make claims? We are convinced that farmers are, and that their efforts need to be better rewarded, so that more of them commit to and massively adopt these practices, in order to have a real impact on mitigating climate change and improving environmental health.

To find out more :

- Farm Foundation, issue report by Alejandro Plastina (May 2022) The U.S. voluntary agricultural carbon markets: where to from here?

- Agridées, Note de think tank, Marie-Cécile Damave (May 2022) Agriculture: reconciling economic profitability and climate action

- Farm Foundation, video of the Solving the barriers to agricultural carbon markets forum (April 2022)

- Agridées, video of the conference Regenerative agriculture: marketing concept or paradigm shift? (June 2022)

- Farm Foundation, video of the Emerging Carbon Markets in Agriculture: Issues and Opportunities (March 2021)

Footnotes

[1] United States Department of State and the United States Executive Office of the President (November 2021) The long term strategy of the United States – Pathways to Net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050

[2] White House (November 2022) Opportunities to accelerate nature-based solutions: a roadmap for climate progress, thriving nature, equity, & prosperity

[3] See the dedicated USDA page: https://www.usda.gov/climate-solutions

[4] See ADM website: Second Year of ADM re:generationsTM Brings additional incentives and choices – USDA grant helps ADM expand state programs (June 30, 2023)

[5] See the announcement of July 21, 2022: ADM, Farmers Business Network to expand sustainable AgTech platform

[6] On this point, see the article published on the Terrasolis website on March 10, 2022: Low Carbon Label and SBTi, what are the synergies and challenges?

This blog was co-written by Agridées Head of Innovation and International Affairs Marie-Cécile Damave and Farm Foundation Vice President of Programs and Project Martha King, both of whom served as moderators at the event. The version in French can be found at Agridées.

Photo courtesy of Marie-Anne Omnes – Agricultural Specialist, Office of Agricultural Affairs, U.S. Embassy of the United States.